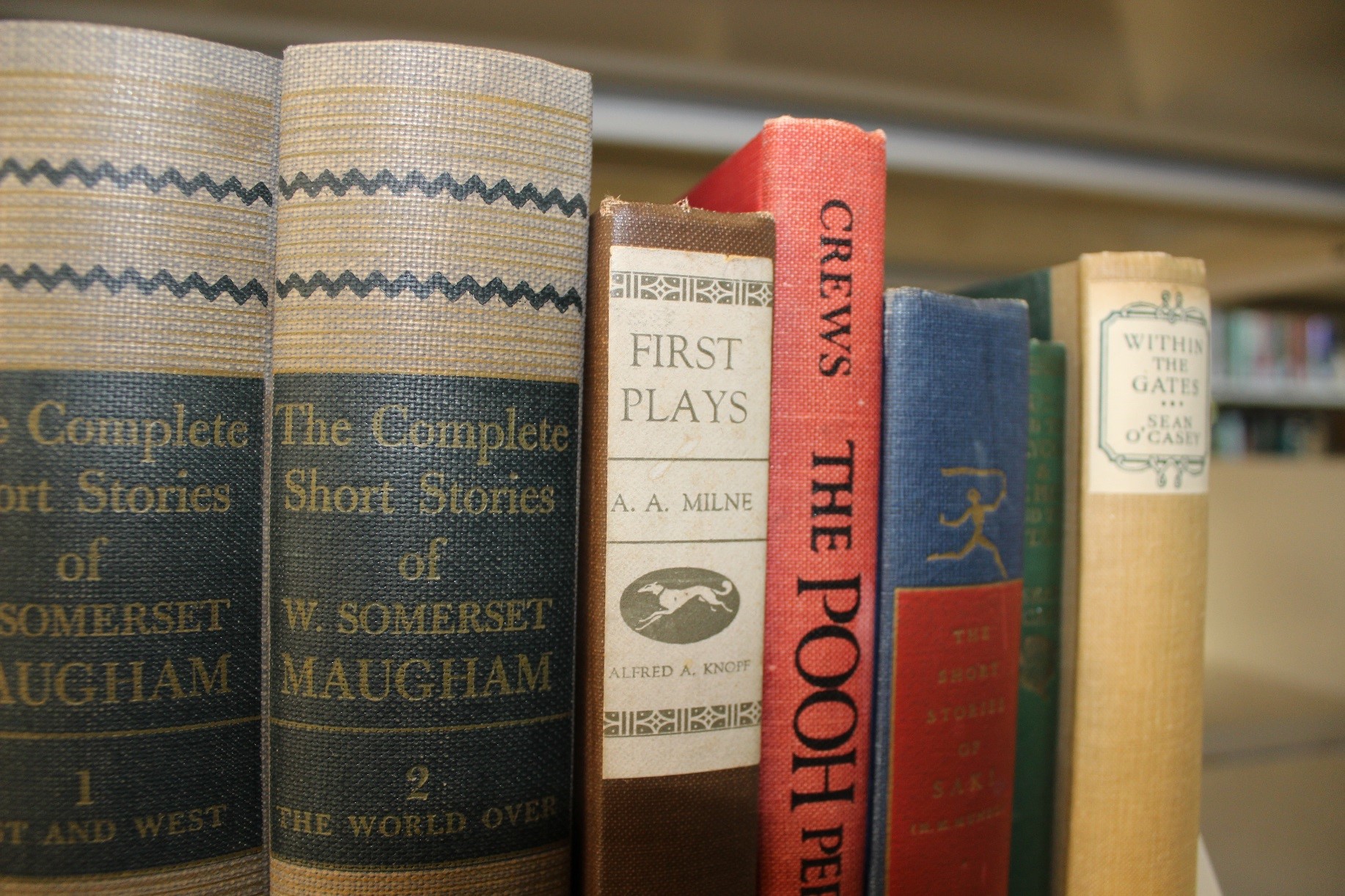

A.A. Milne (1882-1956) is an English author who is best known as the creator of Winnie-the-Pooh. Deep in the Southampton Stacks, however, hides an example of Milne’s earlier work. Milne’s First Plays was published in 1919, a transitional period of his life. He’d begun putting the First World War behind him by contributing to Punch, a literary magazine with a wealth of humor and satire. Milne tells us in the introduction that these plays were written through 1916-1917, a period in which he was enlisted in the military. During this time, Milne wrote plays to raise the morale of his fellow soldiers (Bio). Milne writes that these plays “… would hardly have been written if not for the war.” (ix).

Milne was injured in the Battle of the Somme, a battle similarly experienced by authors J.R.R. Tolkien and C.S. Lewis, both of whom also went on to write many fantastical works. Milne’s First Plays are counter-weighted by silliness and skepticism, just the kind of entertainment enjoyed by soldiers at the time. In the first play, Wurzel-Flummery, two politicians are offered a large sum of money with a small caveat: they must relinquish their reputable last names in exchange for “Wurzel-Flummery”. The Lucky One explores the relationship between two brothers: one the pride of the family, one often passed over. The Boy Comes Home explores a disturbing conflict between a returning soldier and his family’s expectations of him. Belinda is a convoluted romance in which two admirers fight for the affections of an (unbeknownst to them) already married woman. The Red Feathers is unique from the others as it is an operetta with songs.

British troops at the Battle of the Somme which lasted over four months. source.

Soon after, welcoming a child into the world pushed Milne toward writing the children’s books he’d become known for. The first Winnie-the-Pooh book would be published in 1926. Still, as Milne moved from war to fatherhood (and back to war – he served in the British Home Guard during World War II), the experience of conflict never left him. Some argue that Winnie the Pooh is somewhat uneven in that the writing shifts between adult and childish voices and tones. As Niall Nance-Carroll writes:

Milne’s construction of multiple possible points of reader identification helps to support such shifting of modes: the Pooh stories may be read as comic or tragic, depending on which character the reader focuses on. (63)

Milne would soon turn away from children’s books, but remains known for his beloved Winnie-the-Pooh. Let our edition of First Plays (1922) stand as a small testament to the prolific literary career Milne had outside the realm of children’s literature.