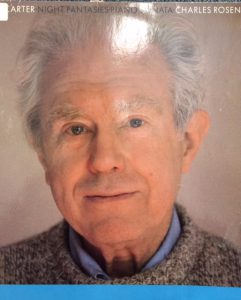

Charles Rosen (1927-2012) was a pianist, author and educator. He was a faculty member of Stony Brook University’s Music Department from 1971-1985. Among his many books, the most famous, The Classical Style (1971; updated by Rosen in 1997), received the U.S. National Book Award, and has been translated into several languages.

He gave the Charles Eliot Norton Lectures at Harvard University in 1980 and ’81. On February 13, 2012, President Barack Obama awarded Rosen a National Humanities Medal “for his rare ability to join artistry to the history of culture and ideas.”

“His writings,” the citation continued, “about Classical composers and Romantic tradition–highlight how music evolves and remains a vibrant and living art.” [i]

The following are among the Music Library’s recordings which attest to his artistry and sustain his legacy:

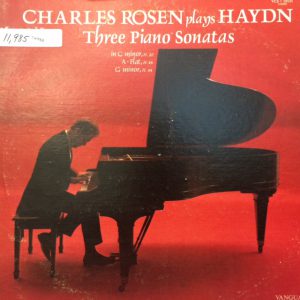

Charles Rosen Plays Haydn : Three Piano Sonatas. New York: CBS Records, 1969. VCS 10131. Music Library LP 11,985.

This album features Piano Sonatas H. 20, H. 46 and H. 44. Franz Joseph Haydn dedicated the virtuosic H. 20 in C minor (1771) to the “Auenbrugge” sisters, who Rosen believes must have possessed exceptional pianistic technique. Rosen sees the work as one where Haydn’s stylistic evolution is clearly evident. The first movement of the H. 46 in A flat major (1788; begun 1767-70) has a leisurely feel and gives the effect of improvisation. It is followed by a dramatic slow movement thought to be inspired by Mozart, and a short Presto finale. The two-movement Sonata H. 44 in G minor (1788; begun 1771-73) “never goes beyond the technical limitations of a style intended for the amateur,” Rosen writes, “while transcending it musically.”

Robert Schumann : the Revolutionary Masterpieces. Charles Rosen, piano. Los Angeles: Elektra, 1984. 79062. Music Library LP 16,609/11.

Rosen considered Robert Schumann (1810-1856) to be “the most personal, most eccentric and in some ways the most individual of Romantic composers…” Schumann, for instance, habitually ascribed his music to his alter egos Florestan (the passionate extrovert) and Eusebius (the reflective introvert). His music, with its unpredictable rhythmic shifts, unresolved harmonies and poetic simplicity, quickly effected a musical revolution during the early nineteenth century. Rosen illustrates this in his performance of six works: Impromptus on a Theme of Clara Wieck, op. 5 ; Davidsbündlertänze, op. 6 ; Carnaval, op. 9 ; Sonata in F# minor, op. 11 ; Kreisleriana, op. 16 ; and Dichtungen für das Pianoforte = Poems for the Piano,op. 17. Rosen performed from the earliest editions of these works “to best represent the originality and range of Schumann’s genius.”

Bach, Johann Sebastian. The Last Keyboard Works: The Art of Fugue, The Goldberg Variations, A Musical Offering: The Two Ricercars. Charles Rosen, piano. New York: Columbia/Odyssey, 1969. 32 36 0020. Music Library LP 7793/95.

This three-disc set contains all of the keyboard music for two hands that J.S. Bach (1685-1750) published or prepared for publication during the last decade of his life. Rosen’s liner notes tell the story behind the Ricercars from Bach’s “Musical Offering.” The loose and informal nature of the three-voice Ricercar, Rosen muses, may represent what Bach recalled of his improvisations for Frederick the Great during a visit to Potsdam, Germany in 1747. The six-voiced Ricercar is the fugue that Frederick the Great asked Bach to improvise upon a theme His Majesty had himself composed. Bach declined the request, went home and composed a six-voiced Ricercar based upon his own, simpler theme instead. It is, as Rosen describes, a deeply expressive work, a glorious moment in the “Musical Offering,” and in “all music of the High Baroque.”

Bach’s “Art of the Fugue,” was published posthumously by his children. It is a series of eleven fugues, four canons and two sets of minor fugues, all based on a simple and austere theme. Rosen calls the “Art of the Fugue,” “one of the supreme works of the 18th century.” It is, he continues, “a summary of the life that Bach had devoted to his art, a demonstration and proof of the contrapuntal power with which he had written for almost half a century.” Rosen’s notes address the possible keyboard instruments that Bach was writing for, and the intended audience of the work.

The Goldberg Variations are, in Rosen’s words, “a survey of the world of secular music.” The theme, called an “Aria,” is a sarabande that Bach had written many years ago for his second wife, Anna Magdalena. The variations include canons from the unison to the ninth (including two canons by inversion), a fugue, a French overture, a siciliana, a quodlibet, accompanied solos, and a series of inventions and dance-like movements. Its dazzling variety of brilliant keyboard effects makes it, Rosen asserts, “the greatest work of keyboard virtuosity before Beethoven.” The three monumental works in this set, he concludes, “are each a demonstration of what can be done with one theme, of how to make the most of the least.”

STRAVINSKY, IGOR. SERENADE IN A ; SONATA FOR PIANO (1924). SCHOENBERG, ARNOLD. KLAVIERSTUCK, OP. 33A AND 33b ; SUITE FUR KLAVIER, OP. 25. CHARLES ROSEN, PIANO. NEW YORK : COLUMBIA, 1969. p14210. MUSIC LIBRARY LP 12,776.

Rosen was also known as a champion of 20th-century music. The first selection on this album, Stravinsky’s Serenade, was started in the mid-1920s, during the composer’s trip to America. Rosen refers to the composer’s autobiography for a description of the work: “The four movements…,” Stravinsky states, “are united under the title Serenade, in imitation of the Nachtmusik of the eighteenth century, which was usually commissioned by patron princes for festive occasions.” The movements are called “Hymne,” “Romanza,” “Rondeletto,” and “Cadenza Finale.” The Sonata was written in 1924, when Stravinsky was beginning to make appearances in public as a pianist and a conductor. “As in all of Stravinsky’s works,” Rosen writes, “the great melodic beauty of the main lines is to be heard throughout the Sonata.”

Schoenberg’s Two Piano Pieces, op. 33a and 33b were composed with the twelve-tone technique. They were written just before Hitler’s rise to power and the composer’s departure for the United States. Op. 33a is built with continuously rising and falling chords, which increase in lyricism and dramatic contrast. Op. 33b is light and spare in style. Both selections are part of the German tradition of short lyric works for the piano, and share a meditative character.

CARTER, ELLIOTT. NIGHT FANTASIES ; PIANO SONATA. CHARLES ROSEN, PIANO. AMSTERDAM : ETCETERA, 1983. ETC 1008. MUSIC LIBRARY LP 16,075.

Rosen and eminent American composer Elliott Carter were good friends. Rosen called “Night Fantasies,” “perhaps the most extraordinary large keyboard work written since the death of Ravel.” The rhythm of the bar lines are not heard in this piece, which Rosen said gives the work its impression of improvisation and freedom. As Rosen’s notes explain, “Night Fantasies,” is full of melody, even some long melodic lines, but it has no themes and no motifs–no tune is ever played twice. Textures recur, however, as do certain intervals and chords, each with a recognizable periodic interval of its own. Carter dedicated “Night Fantasies,” to the four pianists who jointly commissioned it: Paul Jacobs, Gilbert Kalish (also a member of the Stony Brook University Music Dept. faculty), Ursula Oppens, and Rosen.

The complexity and integration of harmony and texture are what make Carter’s Piano Sonata (1945-46), Rosen wrote, such a revolutionary work. It was a radical change in Carter’s style of writing at the time. The sonata and its melodies are built upon the overtone possibilities of the piano. Another radical quality of the work is its rhythm. The changes of time signature are so frequent, Rosen stated, that they were finally left out of the score. The first movement has no time signature. And yet, Rosen found the rhythm of the movement to be “beautifully natural.”

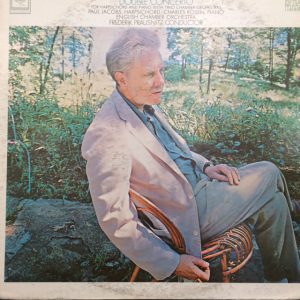

CARTER, ELLIOTT. VARIATIONS FOR ORCHESTRA ; DOUBLE CONCERTO FOR HARPSICHORD AND PIANO WITH TWO CHAMBER ORCHESTRAS. CHARLES ROSEN, PIANO ; PAUL JACOBS, HARPSICHORD ; FREDERICK PRAUSNITZ, CONDUCTOR. NEW YORK: COLUMBIA, 1968. LIS 7190. MUSIC LIBRARY LP 2720.

Igor Stravinsky declared Carter’s Double Concerto to be “a masterpiece.” Carter wrote that the idea of a double concerto was suggested to him by his friend, harpsichordist Ralph Kirkpatrick. Carter then began to focus on the idea of “reconciling instruments,” that have “different responses to the finger’s touch.” He stated further that his efforts “eventually gave rise to the devising of elaborate percussion parts, the choice of instruments for the two orchestras, and a musical and expressive approach that affected every detail.” Other concerns for the composer included the “various relationships of pitched and non-pitched instruments, with the soloists as mediators, and the fragmentary contributions of the many kinds of tone colors to the progress of the sound events.”

Carter’s Variations for Orchestra was composed between 1953 and 1955, to fulfill a commission by the Louisville Orchestra. Instead of the traditional variations form, which is based on one pattern of material, Carter’s Variations are based on three musical ideas. The first two are “ritornelli,” which are repeated literally and then throughout the work in various transpositions of pitch and speed. The third is the central theme, which undergoes many transformations. Contrast is presented in the use of rhythm, diminution, quotation, intervallic expansion, and the use of antiphony between instrumental voices.

[i] Brett Campbell, “Awards and Honors: 2011 National Humanities Medalist Charles Rosen,” National Endowment for the Humanities, https://www.neh.gov/about/awards/national-humanities-medals/charles-rosen (accessed July 12, 2018) ; and liner notes for Robert Schumann, The Revolutionary Masterpieces, Charles Rosen, piano (Los Angeles: Elektra, 79062, 1984).

Gisele Schierhorst

email: gisele.schierhorst@stonybrook.edu

Latest posts by Gisele Schierhorst (see all)

- Brilliant Performances at Art of the Violin - November 17, 2025

- Art of the Violin Opens Its Concert Season - October 23, 2025

- Art of the Violin Concert Delights Everyone - April 21, 2025