A small but rich subset of the Music Library’s sound recordings collection covers many landmark moments in Black history through music, literature, drama, activism and oratory. Below are further details highlighting particular items of interest. More will be added throughout the month:

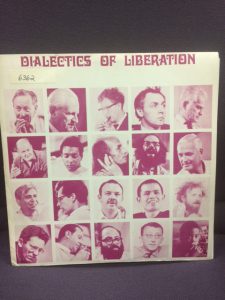

Carmichael, Stokely. Black Power I. Dialectics of Liberation Congress. DL 6. July 1967. Music Library Audio LP 6362.

From July 15-30, 1967, the Institute of Phenomenological Studies in London hosted a Congress entitled the Dialectics of Liberation. Political activist Stokely Carmichael was among the guest lecturers. The 24-year-old Carmichael was raised in the slums of Trinidad, the West Indies, New York City and Washington D.C. where he attended Howard University. Toughened by ghetto life, Carmichael was a militant leader of Howard University’s student government as well as the Chairman of the Student Non-Violent Coordinating Committee. Carmichael’s thoughts flowed continuously before a live audience as he described the differences between “individual,” and “institutionalized,” racism, the struggle for Black power in the United States, and the perpetual fight of nonwhite people for cultural integrity worldwide. He admonished the “spontaneous and inevitable,” proliferation of ghettos in every major city throughout the United States as a “frightening” result of racism. He assailed the imperialism of England and the United States, the “barbaric,” acts of Western civilization and provided many examples of the distortion of Western history.

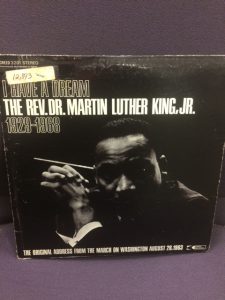

I Have a Dream : Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., 1929-1968: the Original Address from the March on Washington, August 28, 1963. Creed 3201. Music Library Audio LP 12,893.

This album presents speeches recorded live at the 1963 March on Washington. “I am happy to join with you today,” King declared, “in what will go down in history as the greatest demonstration for freedom in the history of our nation.” The March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom took place a century after Abraham Lincoln’s signing of the Emancipation Proclamation. But, as King observed, 100 years later, black society was still crippled by segregation, discrimination and poverty in a nation of vast prosperity. The masterful rhetoric and metaphor throughout King’s famous call for justice are why his “I Have a Dream,” speech has resounded for generations. He invoked the intent of historical legislation (for “all men, yes, black men as well as white men…”), and assessed it against those voiceless black citizens of 1963 suffering “great trials and tribulations…fresh from narrow jail cells,” and living in slums and ghettos, unable to vote or despairing that there is “nothing for which to vote.”

King’s speech appears first on the album but it was in fact last in a string of stirring speeches that day, with many compelling moments, given by other black leaders also deeply involved in organizing the March. The commanding voice of A. Phillip Randolph, head of the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters (the first union led by African-Americans) assured the audience that the March “is not the climax of our struggle, but a new beginning not only for the Negro but for all Americans who thirst for freedom and a better life.” Randolph continued, “Look for the enemies of Medicare, of higher and minimum wages, of Social Security, of federal aid to education and you will find the enemy of the Negro…”

Dr. Benjamin E. Mays gave a Benediction at the March, stating in part, “Here we are God, 180 million people, 100 years after Lincoln freed the slaves, 98 years after the close of a bloody civil war fought to preserve one nation under God indivisibly, 187 years after Jefferson declared that all men are created equal…Here we are God, confused, baffled, floundering, faithless, debating whether the Congress of the United States should pass legislation guaranteeing to every American the equal protection of the law, debating whether its business should have the right to discriminate against a man because thou, oh God, made him Black!”

Bayard Rustin, the chief organizer of the March, read aloud the demands of the March for vocal affirmation by the crowd. Randolph read a pledge of commitment to “the achievement of social peace through social justice,” and urged the crowd to sign pledge cards with their names, addresses and the date. The cards “should be kept and framed and placed in your home for the inspiration of generations to come,” he said.

Roy Wilkins, champion of civil rights and executive secretary of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People said, “We’re here today because we want the Congress of the United States to hear from us in person what many of us have been telling our public officials back home and that is we want freedom now!” Wilkins called for “employment, and with it the pride and responsibility and self-respect that goes with equal access to jobs; therefore we want an F[air] E[mployment] P[ractice] C[ommittee] bill as part of the legislation package.” To the crowd’s approval, Wilkins demanded school desegregation, and for the Justice Department to “speed the end of Jim Crow schools, south and north.” He called for an end to violence, stating, “…All over this land, and especially in parts of the deep South, we are beaten and kicked and maltreated and shot and killed, by local and state law enforcement officers. It is simply incomprehensible,” Wilkins continued, “to us here today and to millions of others far from this spot, that the United States government, which can regulate the contents of a pill, apparently is powerless to prevent the physical abuse of citizens within its own borders.”

Wilkins found President Kennedy’s civil rights proposals at the time, to “represent so moderate an approach that if it is weakened, or eliminated the remainder will be little more than sugar water…We’re tired,” he continued, “of hearing rules cited as a reason why they [i.e. Congress] won’t act. Now we expect the passage of a Civil Rights bill!”

John Lewis, Chair of the Student Non-Violent Coordinating Committee (preceding Stokely Carmichael), and at 24, the youngest of the speakers, began, “We march today for jobs and freedom, but we have nothing to be proud of. For hundreds and thousands of our brothers are not here.” He mentioned Mississippi sharecroppers earning less “than three dollars a day,” working “twelve hours a day,” and “students in jail on trumped-up charges.” Lewis continued, “We come here today with a great sense of misgiving.”

Lewis identified the shortcomings of the proposed civil rights legislation. It provided no protection, Lewis argued, for those engaged in peaceful protest, those who want to vote but lack a sixth-grade education, those who dared register to vote, or equality for “a maid who earns five dollars a week in a home of a family whose income is $100,000 a year.”

Lewis excoriated the state of the American political party system. “By and large, American politics,” he said, “is dominated by politicians who build their careers on immoral compromises and ally themselves with open forms of political, economic and social exploitation…What political leader can stand up and say, ‘My party is the party of principles?’…Where is our party? Where is the political party that will make it unnecessary to march in Washington?”

Finally Whitney M. Young Jr., Executive Director of the National Urban League, chastised those “who would make deals, water down civil rights legislation, or take cowardly refuge in technical details around elementary human rights. They would even now,“ Young Jr. continued, “delay until after Christmas the consideration of these bills before Congress…This March must go beyond this historic moment…Civil rights are not negotiable in 1963.” With such a recording one can easily return to the original moments and contexts where these remarks were first heard.

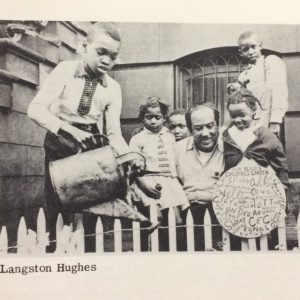

Hughes, Langston. Langston Hughes’ Jerico-Jim Crow. Music arranged and directed by Professor Hugh Porter. Directed by Alvin Ailey and William Hairston. A Stella Holt Production. Folkways Records FL 9671, 1964. Music Library Audio LP 5427/28.

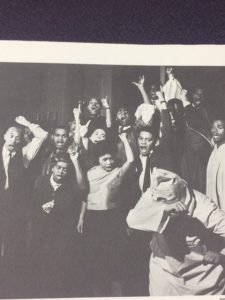

Poet, activist, novelist, playwright and columnist Langston Hughes’ musical, “Jerico-Jim Crow,” with music arranged by Hugh Porter, was performed in New York City’s Village Presbyterian Church and Brotherhood Synagogue to rave reviews by the New York Times in 1964. Many spirituals and traditional songs are included, along with original music. The cast of six is accompanied by a chorus and an instrumental ensemble of piano, organ and percussion.

The emotions behind each historical event are woven seamlessly throughout the play. “Jerico-Jim Crow” begins with an ensemble singing and aspiring to freedom. An old man and woman want to march and vote, eat ice cream at the downtown store, and send their children to the nearest schools and universities. In a series of flashbacks, they recall the horrors of slavery and how it broke up families—a woman cries, “They sold my children away from me,” and a boy sings, “Mama, is Massa gonna sell us tomorrow?’ A man laments, “Oh, God, I can still hear my children’s voices.” When word gets around that some slaves were running away to the North and working with Abolitionists to do away with slavery, he decides to join them. After John Brown’s raid of Harper’s Ferry and the Civil War, and the disillusion experienced during Reconstruction, the ensemble is beleaguered by Jim Crow laws. A character called Jim Crow is played by one actor, in the guises of a trader, Klansman, planter, minister, governor, policeman and jailer. The show ends as the ensemble continues to fight for justice. Names of those engaged in the civil rights movement (W.E.B. Du Bois, Martin Luther King, Jr., Daisy Bates, James Meredith, James Peck, A. Philip Randolph, John Lewis, James Farmer, Roy Wilkins and President John F. Kennedy) are incorporated into the lyrics of one of the musical’s final songs.

Sweet Honey in the Rock (Musical group). Good News. Flying Fish Records. FF245, 1981. Music Library Audio LP 16,473.

Sweet Honey in the Rock is an a cappella women’s vocal ensemble founded by Bernice Johnson Reagon in 1973. The topics sung by the ensemble, with original and traditional music, include cultural, political and personal struggles, spirituality, womanhood, parenting, love and celebration. The group has enjoyed accolades and the loyalty of fans for decades, as can be heard on this album, recorded live on November 7, 1980, at All Souls Unitarian Church in Washington, D.C. With a variety of vocal harmonies, layers and textures, Sweet Honey explores a range of subjects that touch its listeners. Johnson Reagon speaks to the audience and encourages them to join in the performance. The opening song, “Breaths,” conveys the African world view of the connection between the invisible spirit world, man and the visible world of nature; it too explores the relationship between past, present and future. “Echo,” relates the current episodes of political violence and how remindful they are of other historical tragedies. “Chile Your Waters Run Red Through Soweto,” illustrates the thread of violent uprisings in South America, South Africa and Wilmington, North Carolina, USA. “Oh Death,” speaks to the devastation of grief; while “Good News,” celebrates the joys of the Christian faith. “Biko,” is a vocally percussive tribute to South African anti-apartheid activist Steve Biko. “If You Had Lived,” with lyrics and music by Johnson Reagon (as is much of the album) is an examination of conscience—had we lived in the times of those struggling for freedom, what would we have done? “Oughta Be a Woman,” chronicles the sacrifices of Johnson Reagon’s mother for her family, and of women everywhere; “On Children,” reminds us that they are here not to imitate us and our past, but to think for themselves and carry us into the future. The loneliness and yearning expressed in “Time On My Hands,” and “Alla That’s All Right, But,” lead to the comfort and passion of the concluding song, “Sometime.” Despite some retirements, the membership of Sweet Honey has expanded and now includes a sign language interpreter, which is “Good News,” for new generations of listeners.

Anthology of Piano Music by Black Composers. Ruth Norman, piano. Opus One Records. No. 39, 1978. Music Library Audio LP 16897.

Ruth Norman (1928-2007) was a gifted pianist dedicated to educating the public about the contributions of Black composers, from the Renaissance through contemporary periods. Her album proceeds chronologically, and opens with three excerpts from Twelve Country Dances by British composer Ignatius Sancho (1729-1780). “Bushy Park,” “Cuthford Heath Camp,” and “Ruffs and Rhees,” indeed have danceable meters, are very brief and, in the keys of C and G major, are easy enough for a student to play. Philadelphian James Hemmenway’s “Curtsy Cotillion” (1811) is a lively tune in G major, with slight variations in meter throughout the piece. With “Johnson’s Dream Waltz,” in G major by Francis Johnson (1792-1844), one hears the use of the sustaining pedal, seventh chords in the left hand, contrasting use of register, unison and a minor key section, and other traces of a more romantic style. Johnson’s “Victoria Galop,” and Thomas Greene Bethune (aka “Blind Tom”)’s “Oliver Galop,” are sprightly pieces with dry, rapid eighth- and sixteenth-note chords accompanying rapid melodic figures in the right hand. With William Grant Still’s beautiful “Summerland,” (1936), from his suite, Three Visions, one encounters a noticeable sophistication in meter, along with both jazz-infused and impressionistic harmonies. Two movements from Still’s suite Traceries evoke other moods: the quick, repetitive motives of “Muted Laughter,” depict merriment, while the ponderous, low registers in “Wailing Dawn,” with its call and response melody, create an atmosphere of gloom and mystery. Acclaimed British composer Samuel Coleridge Taylor employed a West Indies’ melody in his technically challenging “Bamboula” (African Dance, op. 59, no. 8). William Boyd, of Gaithersburg, Maryland, wrote a “Petite Rondo,” which explores a variety of tonal areas. Haitian melodies and rhythms dominate “Danza Number Four,” by Ludovic Lamothe (1882-1953), a native of Port-au-Prince who was known as the “Noir Chopin.” The final work on the album is Margaret Bonds’s “Troubled Waters,” (1967), which is based on the Negro spiritual “Wade in the Water.” From the outset of this piece one hears the rhythms and call & response of a choral setting, but this leads to unexpected harmonies and a showcase of pianistic virtuosity.

Black Music: The Written Tradition. The Black Music Repertory Ensemble; Michael Morgan, cond. Center for Black Music Research. CBMR001, 1990. Music Library Audio LP 19,386.

This superlative album features the Black Music Repertory Ensemble, which is the performing unit of the Columbia College Center for Black Music Research. The BMRE’s purpose is to promote appreciation for the Black musical heritage through the performance and recording of small-ensemble literature written by Black composers between c. 1800 and the present day. This concert was recorded live on October 13, 1989 at the Sheldon Concert Hall in St. Louis, Missouri.

The accompanying liner notes provide extensive biographical and literary information on each selection. Much of the music is thoughtfully arranged and orchestrated for the ensemble by composer Hale Smith. Philadelphian Frank Johnson’s “Princeton Grand March,” is stately and majestic. Sidney Lambert’s (ca. 1835-1905) “Rescue Polka Mazurka,” is an elegant dance tune in ¾ time. Montague Ring is the pseudonym of British composer Amanda Aldridge (1866-1956), whose “Three African Dances,” reveal distinctly English melodies and harmonic progressions. Will Marion Cook’s (1869-1944) Three Negro Songs (1912) employ the use of Negro dialect, which was first used in the days of minstrelsy. Its use was later rejected by some intellectuals but still used by others for artistic effect:

“Come along Mandy, come along Sue,

White folks watchin’ an’ seein’ what you do,

White folks jealous when you’se walkin’ two by two

So swing along, Chillun, swing along!”

The first song, “Swing Along,” is from Cook’s musical, “In Dahomey,” (1902). “Swing Along,” contains rhythms which first appeared in ragtime music in the late nineteenth century. Baritone Donnie Ray Albert’s masterful upper range, the pronounced lyrics and tight ensemble playing draw eager applause from the audience. The middle song, “Exhoration,” is a slow, heavy recitative in a minor key, with a Biblical message: “Remember, if a brudder smotes dee on de lef’ cheek, turn roun’ an’ han’ him de odder!” and “Rain-Song,” with its rhythmic, brassy accompaniment, details the effect of imminent rain on nature’s creatures.

“St. Louis Grey’s Quick Step,” is a social dance tune by St. Louis’s earliest-known black composer, J.W. Postlewaite, (1837-1889), a former slave who was freed in 1850. Two excerpts follow, from the Noble Sissle (1889-1975) and Eubie Blake (1883-1983) collaboration Shuffle Along: the title tune, and “In Honeysuckle Time.” Shuffle Along premiered in 1921 with an all-black cast, and recently had a brief Broadway revival. The melancholy beauty of N. Clark Smith’s (1887-1933) “Pineapple Lament” reflects the composer’s perception of the island of Martinique and the loss of pineapple groves there after a volcanic eruption. Both the “Lament,” and Smith’s bright, syncopated “Banana Walk,” were well-received by the audience. James Reese Europe’s (1881-1919) “Castle House Rag,” includes “dotted shuffle rhythms,” of the one-step in its first section, and more syncopated rhythms in the contrasting second section. Leslie Adams’s (1932-) setting of Paul Laurence Dunbar’s “Lead Gently Lord…” was composed especially for the BMRE. The album concludes with the patriotic “Spirit of the U.S. Navy,” by Alton Augustus Adams (1889-1987).

Silhouettes in Courage. Various actors. 4 volume set. DOO-DAT Productions. SIL-1000-4000, 1970. Music Library Audio LP 16,487/94.

Silhouettes in Courage presents a detailed history of the Black American experience on record. The project received high praise when it was first released in 1970. Over 500 actors and musicians narrated and reenacted events in Black history, from the earliest cultures and civilizations in Africa to the late sixties. This production would be well-suited to any educational curriculum or to the layperson wishing to learn more about Black history.

Volume 1 is narrated by celebrated actor Ossie Davis, who describes how “industry flourished throughout Africa’s free and independent kingdoms…until the first slave traders landed on Africa’s shores.” There are first-hand accounts of slave auctions, slave treatment and uprisings. The detailed, emotional script was prepared in consultation with historian and Professor William Loren Katz. The music throughout the recording includes an original score and special arrangements of excerpts from Antonín Dvořák’s “New World,” Symphony, and Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky’s “1812,” Overture.

In Volume 2, the dynamic voice of actor Brock Peters, aided by a noble cast, covers the post-Revolutionary period, the Industrial Revolution, the work and courage of Abolitionists, and the events leading to the Civil War. Lesser known facts, people, events and correspondence are dramatized, continuing with the efforts and failures of Reconstruction, Southern resistance to the results of the war and the rise of the Ku Klux Klan. Accompanying music includes excerpts from Howard Swanson’s Concerto for Orchestra and Charles Jones’s Symphony No. 6.

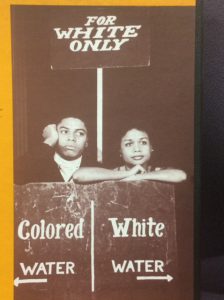

Volume 3, narrated by distinguished actor and director Frederick O’Neal, covers the passing of Amendments 13 through 15, as blacks experience full citizenship in an environment hostile to equality and filled with lingering prejudice, violence and discrimination. Black inventors reach new heights of productivity, and laborers fight for integration and fair union practices. Blacks achieve distinguished military service, and many black cowboys find fame on the frontier. Activists fight for anti-lynching laws, a fair trial by jury, the end of mob violence and the right for blacks to vote without intimidation. Blacks make further gains in education and leadership. The NAACP and Urban League are formed, and there is mounting opposition to Jim Crow laws and segregation.

Volume 4 features narration by acclaimed actress, poet, writer and activist Ruby Dee. Many firsts were accomplished by Black Americans in the first decades of the 20th century in the fields of medicine, politics, sports and entertainment. Jamaican Marcus Garvey promoted “Black pride,” and a “Back to Africa,” movement, as head of the Universal Negro Improvement Association. Political scientist and diplomat Ralphe Bunche’s work in trying to resolve the Arab-Israeli conflict in Palestine earned him the 1950 Nobel Peace Prize. Bunche was later involved in the formation of the United Nations. A new phase of civil rights began when Rosa Parks refused to sit in the back of a Montgomery, Alabama bus and was arrested. A young Baptist minister, Martin Luther King Jr., suggested a city-wide bus boycott, which led to a Supreme Court ruling that Alabama’s laws requiring segregation on buses were unconstitutional.

With the formation of CORE (Congress of Racial Equality) and SNCC (Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee), segregation laws were challenged throughout the country. When Martin Luther King Jr. was jailed in Georgia, presidential candidate John F. Kennedy, with help from his brother Robert, secured his release. John F. Kennedy won the election and wenton to propose civil rights legislation. Malcolm Little, the son of a Baptist Minister, became known as Malcolm X, the most quoted advocate of “Black Pride,” during the 1960s.

On August 28, 1963, the March on Washington became the largest peaceful demonstration in US history. And yet the decade of the 1960s was one of the most violent, with the deaths of Medgar Evers, John F. Kennedy, Malcolm X, Martin Luther King Jr., Robert Kennedy, civil rights workers James Chaney, Andrew Goodman and Michael Schwerner, and the 16th Street Baptist Church bombing in Birmingham that killed four young girls. Shirley Chisolm became the first black woman elected to Congress, and Robert Abernathy assumed the presidency of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference upon King’s death. The listener comes to appreciate the unique perspectives and delivery of those who participated in this thoughtful project, as it was produced just at the end of the decade.

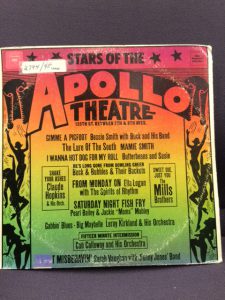

Stars of the Apollo. Various artists. Columbia Records. AL 30789/90, 1973. Music Library Audio LP 2794/95.

On this album’s container, historian Chris Albertson discusses the compelling history of the legendary Apollo Theatre, which is located on 125th Street between Seventh and Eighth Avenues. In 1914, white Harlem residents regularly attended the theatre under its first name, Hurtig & Seamon’s Burlesque, where its Yiddish shows featured performers such as Fannie Brice and Sophie Tucker. When Harlem’s black community expanded downtown around 1930, the Burlesque’s operators changed the theater’s name to the Apollo and started bringing in black talent. The new venue gave another nearby Harlem showcase for black performers, the Lafayette Theatre, some serious competition. Lafayette owners Leo Brecher and Frank Schiffman eventually came to acquire the Apollo and carry on its vaudeville tradition. Even today, as the Apollo presents the very latest in music and comedy, “Amateur Nights,” are still regularly held where performers who don’t meet the audience’s expectations are heartily booed off the stage. (For more information see the Apollo Theater’s web site at: https://www.apollotheater.org/)

At the Apollo, black entertainers gave Depression era audiences music and laughter for the cost of a dime. Since then artists whose success transcended an appearance at the Apollo have returned to acknowledge a debt to the fans who launched their careers. This 1973 collection presents rare, often unissued recordings by individual and group artists, to reflect the kind of acts that were brought to the Apollo stage. As Albertson states in his liner notes, “Many of the performers who appear [on the album] as sidemen have since become headliners,” while “some are all but forgotten.” The recordings range in date from 1927-1964. This unique compilation of vaudeville, show tunes, comedy, jazz and blues is truly enjoyable.

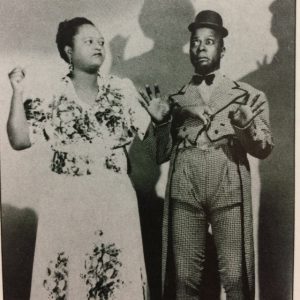

The album begins with Bessie Smith effortlessly transitioning from her usual blues repertory, with a performance of a modern swing tune, “Gimme a Pig Foot (and a Bottle of Beer).” Jack Teagarden, trombone, and Benny Goodman, clarinet, are members of her backup ensemble. In “He’s Long Gone from Bowling Green,” Buck and Bubbles and Their Buckets perform a series of rhymed dialogue interspersed with song. Mamie Smith’s smooth vocals express nostalgia for the sun, birds and family in “Lure of the South.” Vaudevillians Butterbeans and Susie perform “I Wanna Hot Dog for My Roll,” with the accompaniment of a one-string fiddle and piano. Claude Hopkins and His Orchestra play a fast-paced instrumental, “Shake Your Ashes.” The Mills Brothers, who enjoyed fifty years of success and popularity, perform “Sweet Sue Just You,” in four-part harmony, with various vocal effects, including scat singing. Cab Calloway provides the vocals to “Fifteen Minute Intermission,” as he leads his band, whose distinguished personnel include Dizzy Gillespie, trumpet and Milt Hinton, bass.

Chick Bullock performs various voices for the humorous “Reefer Man,” backed by Baron Lee and the Blue Rhythm Band. Anna Robinson, who portrayed “Aunt Jemima,” in person to advertise pancake mix for Quaker Oats in 1933, recorded the “Harlem Woogie,” which also features some scat singing and stride piano. Robinson was accompanied by Jimmy Johnson and His Orchestra. Bill “Bojangles,” Robinson (no relation to Anna), who would later appear with the likes of Shirley Temple and Lena Horne on film, supplied mellow vocals and a tap dancing solo for “Doin’ the Low Down,” with Don Redman and his Orchestra. The song is an excerpt from Lew Leslie’s 1928 musical, Blackbird. Earl Hines, called by Count Basie “the greatest piano player in the world,” performed “Rhythm Rhapsody,” with its change of mood and minor key. “Backwater Blues,” with Ruby Smith, vocals, and Jimmy Johnson and His Orchestra, features Henry Red Allen on trumpet. A nineteen-year-old Ella Fitzgerald recorded “All My Life,” with Teddy Wilson and His Orchestra. “From Monday On,” is sung by Ella Logan, supported by the Spirits of Rhythm.

A classic blues composition, “When My Baby Left Me,” is performed here by Eddie “Cleanhead,” Vinson with Cootie Williams and His Orchestra. Oran “Hot Lips,” Page provided vocals and solo trumpet on the humorous “I Got An Uncle in Harlem,” backed by his Orchestra. A goofy song, “Sploghm,” is rendered by Slim Gaillard and his Flat Foot Floogie Boys (performed with guitar, vocals, piano and drums). A woman worries her man will cheat on her during a “Four Day Creep,” as sung by Ida Cox and Her All-Star Band. The “Stars,” in the Band include bandleader Fletcher Henderson on piano and renown vibraphonist Lionel Hampton on drums. Billie Holiday was twenty-seven when she recorded the upbeat “Wherever You Are,” with Teddy Wilson, piano, conducting his Orchestra. Jimmy Rushing, for many years the esteemed singer with the Count Basie Band, performed “Lose the Blackout Blues,” with Basie conducting from the piano. “Stop You’re Breaking My Heart,” was recorded by Maxine Sullivan, vocals, along with Claude Thornhill and His Orchestra.

Louis Jordan’s song, “Saturday Night Fish Fry,” is introduced with a funny dialogue between actress/singer Pearl Bailey and standup comedienne Jackie “Moms,” Mabley. Ray Nance’s seasoned vocals do justice to the wry “You’re Just An Old Antidiestablishmentarian-Ismist,” with Duke Ellington and his Orchestra. The Fats Waller classic, “’Ain’t Misbehavin’,” is given fine treatment here with vocals by the elegant Sarah Vaughan, and Jimmy Jones’s Band, featuring none other than Miles Davis on trumpet. Little information is known about alto saxophonist Bobby Brown—his composition “Venus Velvet,” performed by his Quartet, has appealing elements of the avant-garde jazz sound that was popular during the 1960s. The theatrical Screamin’ Jay Hawkins performed his most commercial success, “I Put a Spell On You,” with his band. The Apollo collection ends with a twenty-two year-old Aretha Franklin singing a lively rendition of “Evil Gal Blues,” with a gospel accompaniment of brass, piano, organ, harmonica, double bass and drums. This stellar production is a fitting tribute to the many talented artists who have graced the Apollo stage.

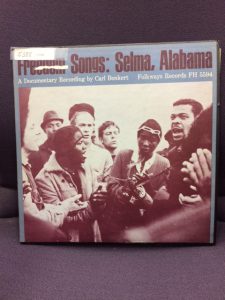

Selma Freedom Songs : a documentary recording by Carl Benkert. New York: Folkways Records. FH5594, 1965. Music Library Audio LP 5388.

In March 1965, with the goal of registering black voters in the South, civil rights protestors made an historic March from Selma to Montgomery, Alabama. Historian Carl Benkert recorded much of the chanting and singing that took place during the March’s vigils, prayers, speeches and protests. The first three songs on the album, “God Will Take Care of You,” “Climbing Jacob’s Ladder,” and “Steal Away,” are sung in unison, with a leader calling out the lyrics. “Nobody Knows the Trouble I’ve Seen,” is introduced as “the song of a share-cropper.” A group of women supply some harmony for the spiritual “Come By Here,” (or Kumbaya). The songs were in many cases contemporized for the civil rights issues at hand. “Berlin Wall,” refers to a barricade erected by police to define an area off limits to protesters. The lyrics to “We Shall Not Be Moved,” address Selma Mayor Joseph Smitherman ; Alabama Governor George Wallace, and Selma Sherriff Jim Clark, all of whom all in office at the time of the March. Rhythmic clapping accompanies “Oh, Freedom,” and “If You Miss Me on the Back of the Bus.” Unison alternates with 2-part harmony on “Woke Up This Morning With Freedom on My Mind.” A male soloist is accompanied by a group of women and children for “Which Side Are You On, Boy?” Children are the lead singers for “Keep Your Eyes on the Prize.” The song “Everybody Wants Freedom,” is sung to the tune of the gospel song, “Amen.” There is call and response as half the crowd chants, “Freedom!” and the other half chants,”Now!” The spiritual “Go Tell It on the Mountain,” is sung with references to Clark, Wilson Baker, Selma’s Public Safety Director, and Al Lingo, a colonel in charge of the state’s highway patrol. A reprise of “Which Side Are You On, Boy?” appears with newly improvised lyrics.

The refrain of “Oh, Wallace,” makes a pointed message to the governor:

Oh Wallace, you never can jail us all!

Oh Wallace, segregation’s bound to fall!

The spirited “Get On Board,” is followed by a children’s rendition of “Ain’t Gonna Let Nobody Turn Me Round,” whose lyrics specify the deterrents the activists are up against (“tear gas,” “horses,” “George Wallace”). During a prayer service, “This Little Light of Mine,” segues into “Which Side Are You On, Boy?” the chanting of “Freedom! Now!” and “Come By Here.” The album closes with a medley which includes the iconic gospel song, “We Shall Overcome.”

![]()

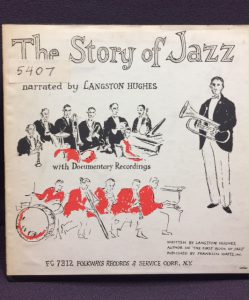

Hughes, Langston. The Story of Jazz/The First Album of Jazz : for Children, with Documentary Recordings from the Library of Folkways Records. Narrated by the Author. New York: Folkways Records. FC 7312. Music Library Audio LP 5407.

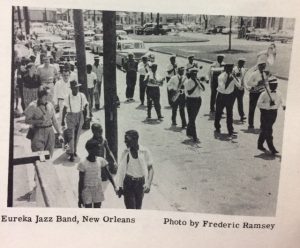

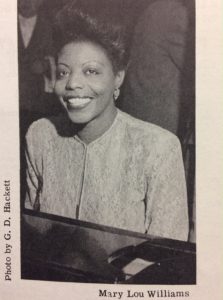

The Story of Jazz is a simplified history meant for children but proves to be just as entertaining and informative for adults. Hughes’s narrative begins with the African origins of music, and continues with the development of jazz, the blues and ragtime in the southern United States, particularly New Orleans, and later in Chicago, Memphis, Kansas City, and New York. The libretto is interspersed with musical excerpts performed by such legendary musicians as Jelly Roll Morton, Louis Armstrong, Ma Rainey, Bunk Johnson, Scott Joplin, Duke Ellington, Dizzy Gillespie and Mary Lou Williams. Characteristics and features of jazz, such as syncopation, improvisation, breaks and riffs are described as well.

Gisele Schierhorst

email: gisele.schierhorst@stonybrook.edu

Latest posts by Gisele Schierhorst (see all)

- Brilliant Performances at Art of the Violin - November 17, 2025

- Art of the Violin Opens Its Concert Season - October 23, 2025

- Art of the Violin Concert Delights Everyone - April 21, 2025